Standing Up For Epilepsy and Brain Tumours by Tammy Karatchuk

Sometimes Getting What You Want Can Be Terrifying

A 3D render of a brain on a purple background.

In March 2009, I was accepted into the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech (formerly Red River College). After six previous attempts over 13 years, I could pursue my dream career as a broadcast journalist.

But I kept my focal onset seizures and history of adolescent brain tumours secret from the instructors and Creative Communications coordinator. I believed my seizures – that I’ve had since 1991 – would be viewed as a flaw and weakness. Media is competitive, and the competition kicks off the moment you step into RRC. I didn’t want the other students to view me as a punchline or incapable. But - like them - I earned my spot. I wrote the Creative Communications admissions exam a week after a seizure. With two minutes left, I handed in the exam. I still had to prove I belonged.

Someone Should Know Your Story

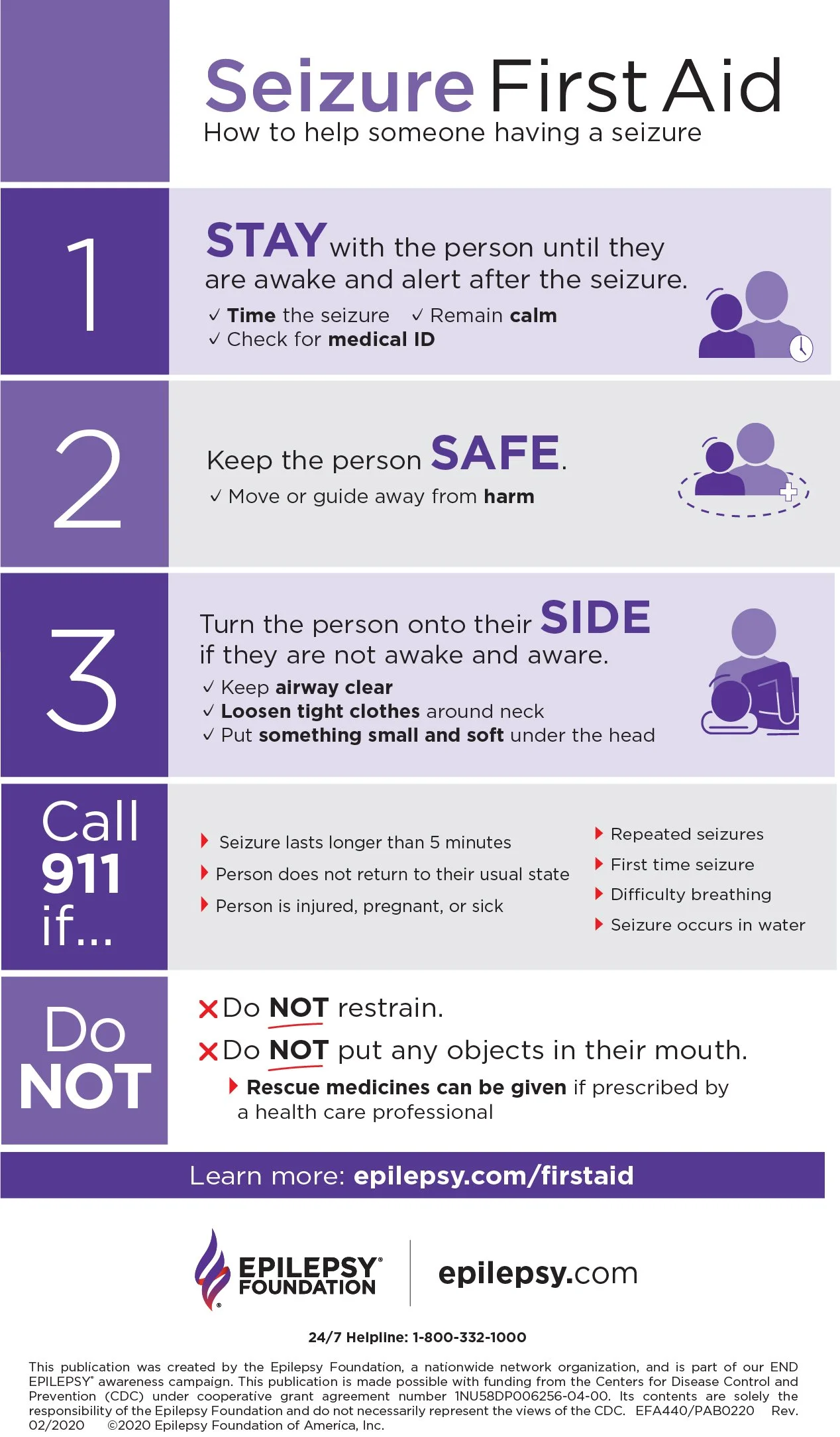

An infographic explaining how to help someone having a seizure: 1. Stay with the person. 2. Keep the person safe. 3. Turn the person onto their side.

While it worked in my favour and the focal onset seizures were on hiatus, someone should know about your seizures. At college, I told a handful of trusted friends about my history, but not my fears. I pretended the past didn't affect my present and wouldn't impact my future.

You need a support system when you’re overloaded with work and your brain is spinning with worry. There are campus counsellors who will provide you with a sense of calm in the storm.

It’s also important for your friends and co-workers to be aware. Before I left my job to enter Red River College, I had a seizure and I couldn’t come to work for three days. Prior to that seizure, my employer and co-workers didn’t know about my seizures. They were supportive and caring. My human resources person asked me, “What can we do to support you?” They didn’t outcast me, and they wanted to learn about my seizures.

But I wish I had carried that lesson into college. Because you’re not different. That’s my hindsight, and I hope someone takes this as their foresight.

School was stressful - but I thought I was lucky. My annual neurology appointments were during the summer, and I didn’t have to miss school. I was pushing myself to the max. Spending twelve to fourteen plus hours at school or on assignment, staring at computer screens or in edit suites. I lined up interviews and met deadlines. My first stand-up took 45 minutes to shoot, and my instructor chose mine as the best one. Happiness turned to terror because I had to sustain that standard.

I needed a support system but I was too afraid to reach out, even to a friend. I feared if I spoke to anyone my vulnerabilities could be seen as a weakness.

Tammy in an editing booth, speaking into microphone with computers and equipment in front of her.

Not having that support system came at a cost. With my brain being set on high stress for so long, it wasn’t used to a lower gear. Two weeks after I left college, I was a reporter at a small paper 45-minutes outside Winnipeg. Thrilling, because it was the same one national Global News anchor, Donna Friesen, started her career.

However, on what should’ve been my second day, I had a focal onset seizure before I left home. I was grateful I hadn’t left home, but I dreaded calling my boss. And my instincts were right because he didn’t believe me. He thought this was an excuse and said my reference didn’t say I had seizures. When I told him I would be losing my driver’s licence – protocol in Manitoba – he wanted proof.

Then an ambulance took me to the hospital.

That was two weeks before convocation. Despite everything, I consider my diploma and Red River College alumni pin an accomplishment. It took 13 years and seven tries for this piece of paper. And I was determined, seizures or no seizures, to be an on-air reporter. I’d show them. I just didn’t know who “them” was.

Secrets Either Make Or Break You

In September, I accepted a 10-month contract with Shaw TV Edmonton. But I had to send Shaw a photocopy of my licence, which I'd already sequestered. My other concern was whether my previous medical suspensions be on my abstract. I didn’t have a licence, just an ID card. I called an instructor, and she said, “If they ask, it’s none of their business.” Luckily, they never asked and I moved to Edmonton.

Tammy reporting on Shaw TV.

I did a story to promote the Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada’s Spring Sprint (now Brain Tumour Walk) and their Edmonton promotions person asked if I’d like to emcee. Partly excited, partly terrified, I accepted. Do I admit I’m a two-time brain tumour survivor? At the Spring Sprint, I probably squished the mic as I told the audience I was a brain tumour survivor. They clapped, and I joked, “Trust me, that wasn’t my parent’s reaction when they found out.”

News travels fast and the next day in the newsroom one of the reporters said, “I didn’t know you had brain surgery. I never would’ve known.” That comment is one of the reasons some people don’t disclose their brain tumours. We fear judgement and the stigma. What should someone who had a brain tumour – and/or epilepsy and seizures look like?

Tammy at the HSC's Epilepsy Monitoring Unit, showing the nodules attached to her head in 2016.

We need to erase our preconceived notions of invisible diseases. These days, I’m open about my epilepsy. During my 40th blogging birthday challenge, I unexpectedly stayed at the Health Science Centre’s Epilepsy Monitoring Unit. I posted photos of myself with 37 nodules on my head and reviews about the food. I even shared a short video after a seizure. In 2016, I became a Purple Day Epilepsy Ambassador for the Anita Kaufmann Foundation.

If people with epilepsy, brain tumours and/or seizures want change, we need to lead the way. We need to educate others to make change. For example, the media requires applicants to have a licence. Not everyone with epilepsy and seizures holds a licence. It’s a Catch-22. You have the skills, but you can’t apply for the job because you don’t have a piece of laminated plastic.

My advice: apply to those jobs. You should be judged on your worth, skills, and determination.

When you are aiming for your dream career, you can feel invisible and alone withholding a secret. But, I encourage you to talk to the faculty or a counsellor. Be open with someone about your epilepsy or brain tumour – or any invisible disease. They can provide a safe haven where you can cope. Tell someone you’re close to at your schools, workplaces, groups and communities.

How Do We Erase The Stigma?

We can start with education and awareness.

When some people hear “epilepsy,” they may think of tonic-clonic seizures - formerly grand mal from television. Tonic clonic seizures are a sliver of what our disease encompasses. Focal, absence, PNES, myoclonic. Plus there are over 130 types of brain tumours, both of mine were different classifications.

According to the Canadian Best Practices Portal, epilepsy is the third most common neurological disease in Canada. However, epilepsy and seizures receive a low amount of media attention. The more we discuss seizures and brain tumours, the less we’ll fear them. One in ten Canadians will have a seizure in their lifetime, and 27 people in Canada are diagnosed with a brain tumour every day.

Sometimes people with epilepsy and seizures feel lonely and isolated from society. Purple is the colour of loneliness. On March 26th, an awareness campaign called Purple Day encourages people to wear purple and open a discussion around seizures. The hope is to destigmatize the disease.

If my instructors or coordinator knew about my seizures, my Creative Communications experience could’ve been different. Maybe an instructor would’ve told security to check on the person in the radio booth or edit suite every hour. Maybe when the instructors would send journalism students to gather interviews, they would’ve asked where I planned to go. In the media industry, your assignment editor sends you to cover certain stories. They know where you are, so why shouldn’t instructors?

But I chose to live in panic mode.

Today, I talk freely about living with epilepsy and my history with brain tumours. My life changed overnight and seizures will impact the rest of my life. When you share your story, sometimes you’re helping others who are struggling. Sometimes you’re helping a person in the same situation as you.

Because everyone has a story.

About the Author

Tammy smiles at the camera, wearing a hat and a purple shirt.

Tammy Karatchuk is a freelance reporter, author, blogger, actor, model, and competitive skater in Winnipeg, Manitoba, originally from Arborg, Manitoba. She holds a Creative Communications diploma, majoring in journalism, from RRC Polytech.

She’s worked with Shaw TV Edmonton, the Edmonton Journal (freelance figure skating and football reporter), 680 CJOB, ChrisD.ca, and Interlake Publishing.

Explore Possible

This blog post is part of Explore Possible, an initiative by Manitoba Possible to amplify stories, perspectives about disability, accessibility, and inclusion.

Read more at manitobapossible.ca/explore-possible or continue on to our latest posts by clicking the titles and arrows in the bottom corners!